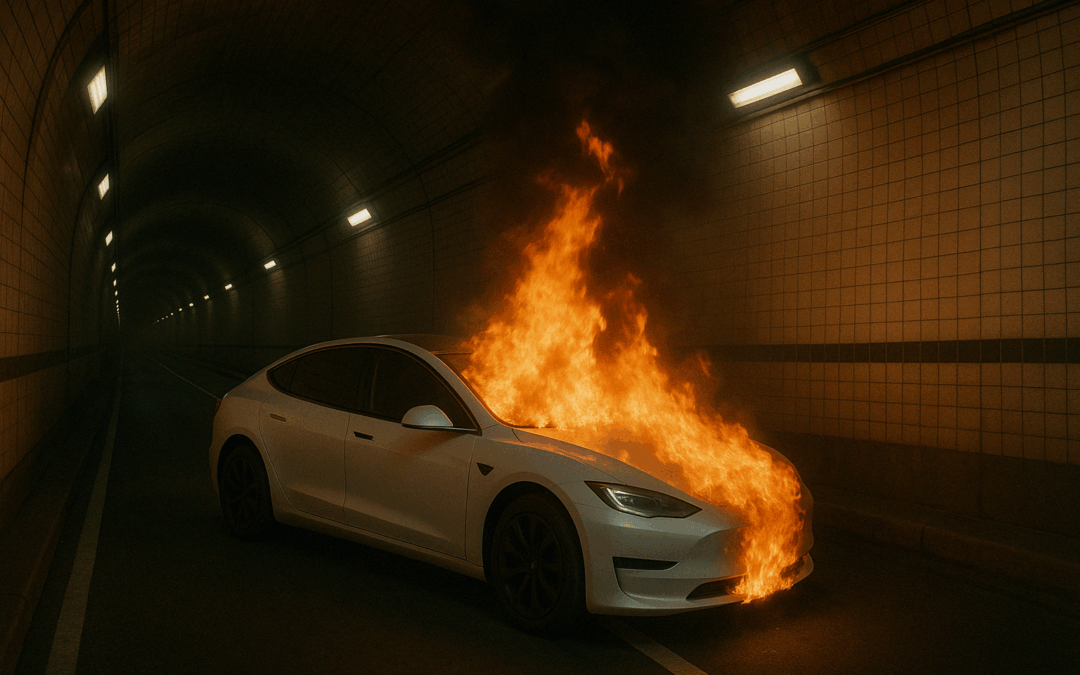

The Lithium-Ion Learning Curve: What We’re Still Figuring Out About Battery Fires

I sat down again with The HazMat Guys’ Bobby Salvesen and Mike Monaco, and what started as a casual check-in about conferences and training quickly turned into one of the most honest conversations we’ve had about lithium-ion batteries. If you work in hazmat or fire services, you’re already hearing about these incidents popping up more and more. Mike’s been teaching metering out in Georgia, and Bobby just came back from South Carolina. But batteries – specifically damaged, smoking ones – stole the show.

Here’s what we learned. And unlearned.

“We’re Building This Plane While We Fly It”

One of the biggest truths that came out of the episode is that nobody has all the answers yet. Not even the guys who are responding to lithium-ion battery incidents three times a day. And that’s okay.

“We really don’t know anything. We don’t trust anything. Hell, we don’t even trust what we’re seeing,” Mike admitted after describing a scenario where they tried to cool a battery by repeatedly dunking it in water.

That approach? Not working.

Instead of resolving the issue, it was creating a cycle: the battery cools, then reignites once it dries off. Then cool again, reignite again. And on and on.

Water Might Not Be the Hero You Think It Is

Traditionally, water is the firefighter’s best friend. But lithium-ion batteries don’t care about tradition. While putting out visible flames with water is still common, the real issue is thermal runaway – the self-sustaining chemical reaction inside the battery that just keeps going.

Mike shared an incident where a battery inside a scooter was removed, dunked under a hydrant, and still began to smoke more aggressively once disassembled. The automatic reaction? More water. But that didn’t solve the problem.

“You’re not stopping the reaction,” Mike said. “It’s going to do its thing until it’s done.”

So why not skip the rinse-and-repeat and contain it instead?

The Case for Overpacking

That leads us to the alternative: overpacking. Bobby and Mike both brought up the idea that if we know the battery is already going bad, maybe we should stop trying to save it and instead focus on isolating it.

“There’s a misconception between thermal runaway and propagation,” Bobby explained. “We cannot stop thermal runaway. But we can stop propagation.”

Translation? The runaway reaction is going to happen. But we might be able to stop it from spreading to other cells.

One method they keep going back to is using cell block containment systems – specialized containers that are supposed to withstand extreme heat and keep everything inside. But even that’s not perfect.

They tested four battery cells inside a 16-gallon drum packed with cell block. One cell popped. The drum’s lid blew off. Repeatedly. The cell block went everywhere.

“Like a popcorn popper,” Bobby laughed.

Only, not funny if you’re standing next to it.

The Reality Check: Cell Block Isn’t Magic

Here’s what’s concerning. The cell block didn’t melt. It didn’t encapsulate the fire. It didn’t behave the way manufacturers said it would.

And that raises some serious questions. Is it not getting hot enough? Is it not doing what it’s advertised to do? Do we need to test this stuff more rigorously?

Mike summed it up: “We’re seeing the probability of failure because we’re dealing with so many reps.”

It’s a reminder that one test doesn’t make a truth. It might take a hundred runs to understand the three that go wrong – and those three are the ones that matter when lives are on the line.

Myth-Busting Should Be a Job Requirement

The guys talked about how more departments need to start running their own experiments. Try different things. Challenge the manufacturer claims. See what actually works in your conditions, with your gear, in your district.

Because right now, everyone’s trying to “solve the problem” with limited data and maybe even outdated assumptions.

When Internet Advice Goes Wrong

Mike shared a post going around social media from a Swedish agency that claimed to have stopped thermal runaway by flooding a burning battery pack with 200 gallons of water.

Sounds impressive, right?

But he cautioned against drawing broad conclusions from one-off videos. “We’re seeing all the probability because of the sheer numbers,” he said. Meaning: they’re not guessing what might happen. They’re seeing what does happen. Daily.

You can’t say, “This worked for me once,” and assume it’ll work every time. That’s how people get hurt.

The Bigger Picture: Changing Science Means Changing Training

One of the most eye-opening parts of the episode came at the end, when Bobby dropped a nugget about EPA’s hazardous waste thresholds. Turns out, under RCRA, a corrosive waste isn’t technically classified until its pH drops below 2 or rises above 12.5. Most responders are taught the danger zone is between 5 and 9.

Why does this matter?

Because it means a whole lot of materials we treat as hazardous might not legally be classified that way. That has implications for neutralization, disposal, and even training curriculums.

As Bobby said, “I used to joke about that, but now it’s serious. You can dump anything, if I’m reading that right.”

It’s a perfect example of how standards aren’t just evolving – they’re sometimes contradicting each other. And that’s why constant learning isn’t optional in hazmat. It’s survival.

Final Thoughts: Keep Asking Questions

If there’s one message to walk away with, it’s this: don’t take anything at face value – not even what Bobby and Mike are saying. They’ll be the first to tell you they’re still figuring it out too.

What makes them stand out is their willingness to share mistakes, test ideas, and keep questioning everything.

So if you’re a hazmat responder, trainer, or just someone trying to keep your crew safer, ask yourself:

- What am I doing out of habit that doesn’t make sense anymore?

- Have I tested the tools and tactics I trust?

- What am I reading or hearing that sounds half-true?

Because when it comes to lithium-ion batteries, half-right is all wrong.

Hello. Thanks for this. Has anyone heard of problems with toxic or heavy metals fallout from the smoke ? I believe there was a test being done but last I heard the results hadn’t been released. We have been back and forth about trying to come up with some guidelines for extinguishing (just delaying the burning really) or letting it burn and protect exposures. If anyone has a link or test result to point to please shout it out. Thank you very much !