A Chlorine Close Call: Breaking Down What Went Wrong and Why It Matters

When Bobby forwarded me this near-miss incident report about a chlorine leak, I didn’t hesitate. “This is an episode,” I told him. It had all the hallmarks of a case worth unpacking – not because we enjoy calling out mistakes, but because there’s a goldmine of lessons here for every hazmat responder, fire chief, and command officer.

This isn’t just another Monday-morning quarterback session. It’s about figuring out where things went sideways so you, me, or anyone in our line of work doesn’t make the same errors when it counts.

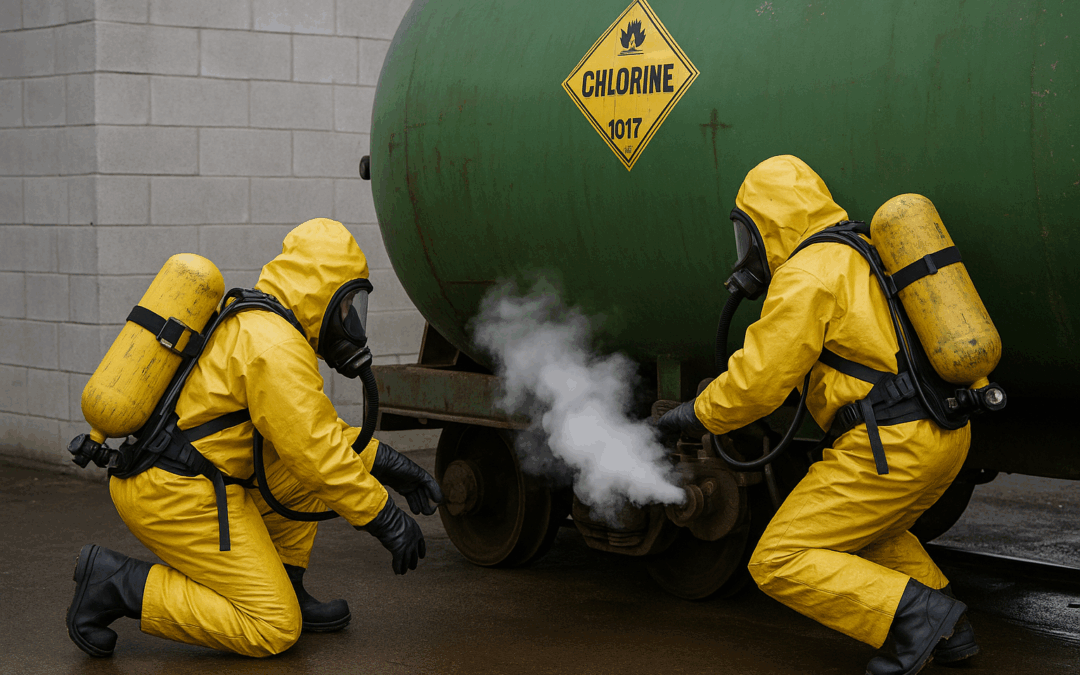

The Incident: A Basic Leak With Serious Consequences

Let’s set the scene: a local company called 911 about a chlorine leak. The fire chief sent out two firefighters. According to the report, they were “awareness-trained.” That’s already a red flag. Awareness-level training teaches you how to recognize a hazardous material situation – not fix it.

The firefighters found a leaking chlorine tank, called the chief (who wasn’t even on scene), and were then told to go on air and shut off the leaking valve themselves. They did. They returned to the station and carried on with business as usual – until days later, when their gear reeked of chlorine and was visibly corroded. The EPA got involved. OSHA got involved. The fire chief resigned. And two seasoned firefighters admitted they’d had sore throats and rashes since the incident.

So, yeah – this wasn’t a small thing.

Awareness ≠ Response

Let’s start with a key detail: training level.

Awareness-trained responders are not supposed to enter the hot zone. Their job is to observe, report, and isolate. That’s it. They’re trained to call it in and back away – not to put themselves at risk or try to mitigate a chemical release.

So how did this end up with two awareness-level firefighters – no backup, no proper PPE – going hands-on with a leaking chlorine tank?

That’s the kind of mission creep that gets people hurt or worse.

Operations-Level: What They Could Have Done

Now, if they were operations-level trained, the most they should have done is:

- Set up isolation zones

- Take readings from a safe distance using air monitoring tools

- Possibly shut off the leak – but only if it could be done remotely and from a safe, cold zone

This wasn’t that. This was straight-up entry into a contaminated zone, complete with exposure symptoms and gear damage. That’s technician-level territory – full stop.

Command Decisions: You Need to Be There

Another point we hammered on: the chief wasn’t on scene when he made the call.

In any incident, especially hazmat, you can’t command what you can’t see. You don’t make judgment calls on toxic chemicals based on a cell phone description. That’s not command. That’s gambling.

We’ve both seen it before – somebody tries to handle it from a distance to “keep things moving.” But hazmat scenes aren’t warehouse fires or medical calls. They don’t run on instinct or speed. They run on training, intel, and deliberate steps.

The chief assuming command without showing up? That violated basic principles of NIMS (National Incident Management System), not to mention common sense.

Decon: Nonexistent, and That’s a Problem

Let’s talk decontamination, or in this case, the lack of it.

When firefighters returned to the station and their gear still smelled like chlorine days later, that told us one thing: nobody got deconned. Not the gear. Not the responders.

Instead, the SCBAs showed visible corrosion. Gear had to be bagged. And these guys were still wearing that stuff around the station for days.

Here’s the kicker: chlorine is an oxidizer and corrosive. Water reacts with it to produce hydrochloric acid. So spraying it with water only made the situation worse if they even tried that. Proper decon would have included stripping gear, isolating it, and conducting medical checks on the guys involved.

PPE: Another Box Left Unchecked

From what we can tell, they were in bunker gear, not chemical suits. Which is another big no-no.

Bunker gear is not designed for chemical environments – especially corrosive gases like chlorine. That’s why we have CPC (Chemical Protective Clothing) and SCBAs rated for hazardous materials. Wearing fire gear into a chlorine leak is like using an umbrella in a hurricane.

And it’s not just about safety during the run. Chlorine embedded in gear is a future fire waiting to happen. As we mentioned, it’s an oxidizer. You take that contaminated gear into a structural fire, and you’re basically wearing a fuse.

Why Doing Nothing Is Sometimes the Right Call

This one really hit home: firefighters are wired to act.

But when you’re facing something outside your training level, the most professional move you can make is to do nothing. Step back. Call for the right team. Let the people with the right tools and the right training handle it.

It’s hard. It feels wrong. But it’s the smart play.

Culture, Accountability, and Training Gaps

What really shocked us wasn’t the leak – it was how many boxes were left unchecked:

- The firefighters had decades of experience.

- They didn’t stop the operation when something felt wrong.

- The department didn’t decon anyone.

- The company and the chief failed to notify the proper agencies.

The Local Emergency Planning Committee (LEPC) eventually found out and reported it to the EPA. That’s when the hammer came down. And rightly so.

This wasn’t a rogue decision or a rookie mistake – it was a systemic failure from top to bottom.

Takeaways Every Department Should Review

We didn’t want this episode to just be a “look how bad this was” kind of story. It’s about learning. Here are the takeaways we hope every responder keeps in their back pocket:

- Know your training level – and respect the boundaries of it.

- Command must be on scene. You can’t direct hazmat ops from your living room.

- Never substitute action for understanding.

- Decon is non-negotiable – even for “small” leaks.

- PPE isn’t optional. If you don’t have the right gear, you don’t go in.

- If something feels off – it probably is. Stop. Ask questions. Document.

For Trainers, Officers, and Chiefs: It Starts With You

This wasn’t just about two firefighters and a bad decision. It’s about departments needing to train better, prepare smarter, and build a culture where stopping the operation isn’t a failure – it’s professionalism.

Leadership sets that tone. If the top guy doesn’t respect training boundaries, that trickles down. And if we don’t change that, we’re going to keep reading stories like this.

Final Thoughts: Every Near-Miss Is a Second Chance

This call could have ended so much worse. Chlorine leaks don’t always give second chances. These guys got one – and so did their department.

What we do next is what matters. Use this incident. Talk about it. Ask questions. Be the one in your department who says, “Hold up, are we doing this right?”

If you’re a chief, a probie, or somewhere in between, you owe it to yourself and your crew to get hazmat right.

Want to Learn More?

- 📘 Check out our new book: The National Emergency Response Hazmat Drills (NERD) on Amazon – packed with 50 drills to sharpen your skills.

- 🧠 Host a training with us. We’re hitting conferences across the country. Visit thehazmatguys.com to book a class.

- 📲 Join the conversation on Facebook or shoot us your thoughts at feedback@thehazmatguys.com.

🎧 Listen to the full episode and others on Spotify, Apple, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Thank you for publishing this incident there seems to be a lack of caution regarding corrosive gases and the toll in takes on unprotected firefighters and their gear. Entering a corrosive

gas environment for plumbing, is unnecessary and negligent.